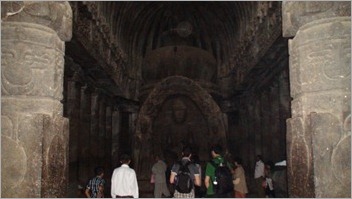

The Viswakarma cave is also known locally as the Sutar ki jhopdi owing to the construction style. This is the only Chaitya in these series of caves., constructed around 7th century A.D. And though not so magnificent in its proportions or decoration, it is still a splendid work with a large open court in front surrounded by a corridor, the frieze above its pillars is carved with various representations.

The Viswakarma cave is also known locally as the Sutar ki jhopdi owing to the construction style. This is the only Chaitya in these series of caves., constructed around 7th century A.D. And though not so magnificent in its proportions or decoration, it is still a splendid work with a large open court in front surrounded by a corridor, the frieze above its pillars is carved with various representations.

The inner temple, consisting of central naïve and side  aisles, measures 85 feet in length, 43 feet width and 34 feet height. The naïve is separated by the aisles by 28 octagonal pillars, 14 feet in height, with plain bracket capitals, while two more square ones just inside the entrance support the gallery above and cut off from the front aisle. One of the pillars is inscribed with the date Saka 1228, which is equivalent to 1306 A.D. One interesting aspect of this chaitya is the missing horse shoe style of façade that we find in other locations like Ajanta or Bhaja.

aisles, measures 85 feet in length, 43 feet width and 34 feet height. The naïve is separated by the aisles by 28 octagonal pillars, 14 feet in height, with plain bracket capitals, while two more square ones just inside the entrance support the gallery above and cut off from the front aisle. One of the pillars is inscribed with the date Saka 1228, which is equivalent to 1306 A.D. One interesting aspect of this chaitya is the missing horse shoe style of façade that we find in other locations like Ajanta or Bhaja.

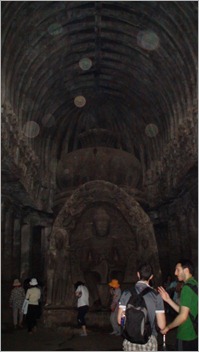

The back of the naïve stands a huge stupa nearly 27 feet in height and 16 feet in diameter. It has simple circular base, hemispherical dome and a s

The back of the naïve stands a huge stupa nearly 27 feet in height and 16 feet in diameter. It has simple circular base, hemispherical dome and a s quare capital as we find in the typical stupa. Typical to a Mahayana construction, it has a large frontispiece nearly 17 feet in height attached to it, on which is a 11 feet colossal Buddha seated with his feet down, and his usual attendants, while on the arch over his head is carved the Bodhi Tree, with dwarfs on either side.

quare capital as we find in the typical stupa. Typical to a Mahayana construction, it has a large frontispiece nearly 17 feet in height attached to it, on which is a 11 feet colossal Buddha seated with his feet down, and his usual attendants, while on the arch over his head is carved the Bodhi Tree, with dwarfs on either side.

The arched roof is carved in imitation of wooden ribs, each rising from behind a little Naga bust, – alternatively male and female, – and joining a ridge piece above. It can be assumed that this style of imitation is a development stage in rock cut architecture, i.e. instead of the typical wooden ceiling the original construction itself was cut in rock. We can trace the sequence of chaitya construction from the early wood-fronted examples at Pitalkhora, Kondane, and Bhaja, through the stone fronted caves of Bedsa and Karla, to  the elaborately decorated ones at Ajanta, and finally to this where it loses nearly all the external characteristic features. To understand more about construction patterns of Buddhism, please read my related post.

the elaborately decorated ones at Ajanta, and finally to this where it loses nearly all the external characteristic features. To understand more about construction patterns of Buddhism, please read my related post.

The deep frieze above the pillars  is divided into two belts, the lower and narrower carved with crowds of fat little ganas in all sitting positions. The upper is much deeper, and is divided over each pillar so as to form compartments, each containing usually Buddha with two attendants, Padma

is divided into two belts, the lower and narrower carved with crowds of fat little ganas in all sitting positions. The upper is much deeper, and is divided over each pillar so as to form compartments, each containing usually Buddha with two attendants, Padma pani and Vajrapani. Needless to say that worshippers used to chant hymns and prayers in chaitya halls and the arched structure echoes nicely. It is said that if we visit this cave early in the morning, any loud voice will echo 3-4 times spanning around a minute.

pani and Vajrapani. Needless to say that worshippers used to chant hymns and prayers in chaitya halls and the arched structure echoes nicely. It is said that if we visit this cave early in the morning, any loud voice will echo 3-4 times spanning around a minute.

At the ends of the front corridor are two cells and two chapels with the usual Buddha figures. From the left end of the back corridor a stair ascends to the gallery above, which contains an outer one above the corridor and an inner one over the front aisle, separated by the two  pillars that divide the lower portion of the great window into three lights. From the outer area, too, small chapels are entered, each containing sculpture of Buddha mythology, and where the very elaborate head-dresses of the females of the period may be studied. Over the chapel to the right of the window is a remarkable group of little fat figures, and the projecting frieze that crowns the façade is elaborately sculpted with pairs of figures in compartments. High up on each side are two small chapels, difficult to access.

pillars that divide the lower portion of the great window into three lights. From the outer area, too, small chapels are entered, each containing sculpture of Buddha mythology, and where the very elaborate head-dresses of the females of the period may be studied. Over the chapel to the right of the window is a remarkable group of little fat figures, and the projecting frieze that crowns the façade is elaborately sculpted with pairs of figures in compartments. High up on each side are two small chapels, difficult to access.

In this balcony, there remains to be noticed the only inscription at all of an early date found among the Buddha caves here; but it is only the mantra (hymn) of the Mahayana school, caved in characters of perhaps the eight or ninth century. It reads:

Ye dharma hetu prabhava hetum, tesham tathagato, hyavadattesham cha yo nirodha, evam vadi mahasramanaa(h).

All things proceed from cause; this cause has been declared by the Tathagata; all things will cease to exist; this is that which is declared by the great Sramana (Buddha). This same inscription is found in other locations like Sarnath, Kanheri, Afghanistan, Burma, Singapore, and Java and is well known in Buddhist literature of Nepal, Tibet, China and Sri Lanka.

We will now move on to Cave 11, which is interestingly without any relation is known as the Do Taal.